I was lucky enough to get an early view of the new Weston Open Living Lab that the Open University (OU) Milton Keynes (MK) has created to tackle crucial sustainability issues. This blog tells the story of my tour…

I was part of a small group of environmental researchers and local enthusiasts who had been invited to experience the first tour of the Open Living Lab on a changeable weather day in June 2024.

My background to the project

I expressed an interest in the Living Lab project after recent work I’d done to support the OU’s Branching Out and TreeLab research projects. I was fascinated to explore the broad synergies that both projects have with this one from the point of view of us seeking to better understand urban treescapes and our (social and cultural) response to them. What intrigued me most about this project however, was the hands-on engagement with the natural environment that it offers the local community to learn from.

My position on the Living Lab project is to help reach as many community organisations and educational providers as possible, but from a personal perspective, I felt a harmonious fit with my two voluntary capacities, Planting Up and Transition Town MK – whose roots are in making positive change happen by taking local, practical action that takes care of our community and the planet in response to the climate and ecological crises.

Naturally, I was eager to see first-hand, how the Living Lab project is exploring the potential for nature-based solutions to help us better understand and deal with the challenges of climate change and biodiversity loss. But I was also excited by the prospect that the project is explicitly inviting us – the MK public – to help co-create it.

Nature restoration: “Wilding”

I first heard about the Living Lab project from a friend who described it as a “wilding” initiative. That description immediately conjured up images of the Knepp Castle Estate for me – the pioneering West Sussex site I’ve been longing to visit for ages, that has managed to turn a failing farm into a profitable destination of extraordinary wildlife abundance just by “letting go” and allowing nature to take over.

Just like Knepp, the concept of nature restoration where you let nature take the driving seat, is the same for the Living Lab. We’re not talking anything like the amount of space that Knepp has to play with here of course, but it is still a sizeable expanse of land.

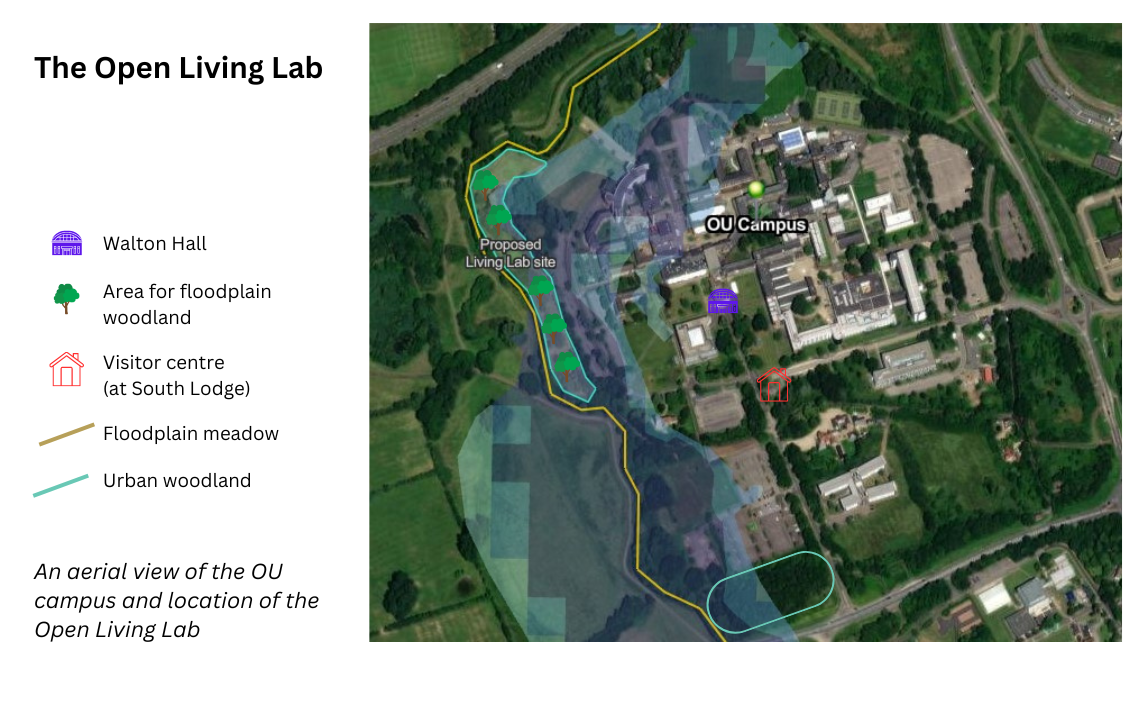

Sitting next to the River Ouzel on the OU’s Milton Keynes campus, the area includes a small woodland and a two-hectare riparian (river bank) area, which is a substantial investment when you consider that equates to about two professional football pitches of land being given over to the project.

Touring the site

We started the tour by meeting at the front of Walton Hall, the beautiful early 19th century manor house that sits at the heart of the Open University MK campus.

We were thrilled to have the Living Lab project leader and senior lecturer in environmental sciences, Dr. Kadmiel Maseyk, as our guide. He made introductions as we sheltered from the rain for a few minutes before we headed down Walton Drive towards the South Lodge.

Putting the project in context Dr Maseyk explained:

“We can’t escape the climate crisis. Still, many people don’t realise the challenge is more complicated than rising temperatures. Climate change and habitat destruction are causing many problems, such as enormous biodiversity loss, fewer pollinating insects, soil erosion, and deteriorating water quality. These issues affect our ability to produce food and other vital services provided by healthy, intact ecosystems. Poor understanding and lack of appreciation for nature are what got us here, so we must act now and find creative ways to engage people with the natural world before it’s too late. This project is vital to improving researchers, students, and the general public’s understanding of how nature-based solutions can address the climate and biodiversity crises.”

The State of Nature 2019 Report found that 41% of species have shown strong or moderate decreases in abundance since 1970 due to habitat loss, climate change and other anthropogenic drivers.

We don’t protect what we don’t know about

This sparked some conversation about a mutual concern for the extent to which people are willing to act or support efforts to reverse declines in wildlife and climate damage, especially when so many of us are becoming increasingly disconnected from nature.

After all, we don’t protect what we don’t know about or understand the importance of. That makes education and engagement like this all the more vital as a way of increasing awareness and connection to nature to help motivate people to support nature recovery.

A 2022 study analysing data from 14,745 adults across European countries including Germany, Spain, France and Italy, researchers found British people have the lowest nature connectedness, a ranking of 3.71 out of a possible 7.

Visitor centre & data hub

On the topic of education, our first stop was the Open Living Lab’s visitor education centre. We didn’t go into the building as it was in the process of being furnished with the appropriate lab furniture, displays and tech, but Dr Maseyk explained how it was being outfitted as a kind of “Command Centre” and dedicated base of operations for receiving groups and running field trips.

We talked about how the visitor centre could be used to deliver classroom instruction, talks and even interactive teaching as a designated learning space to engage local schools and other community organisations with nature recovery education experiences. Ultimately though, it was clear that the onus is very much on knowing what the different groups decide they want from it that will determine how it gets tailored to the different audience needs.

Dr Maseyk went on to tell us about the future intention for resources to be developed catered to different audiences and the dedicated data hub that will be available to secure field data generated through on-site laboratory use as well as through the participation of schools and the public.

The idea is for the data hub to include field data on plant and insect species, carbon sequestration in soils, and tree growth recordings amongst other things, all as part of a digital lab that enables as many audiences as possible to interact with and learn from it (even at distance in true OU style) for the long term.

Monitoring urban biodiversity

Walking about 500 yards further along Walton Drive and into a visitor car park, it was clear to see what a great position the visitor education centre had in relation to the Open Living Lab site.

From the car park we could see the expanse of woodland that was a central part of the Open Living Lab’s demonstration of the benefits of nature recovery action.

As we got closer to the woodland, we could see the edge had a variety of tree species that are probably in the region of 30 to 40 years old.

True to the tenth permaculture design principle, the “edge effect” where the grassland met the woodland, we could see a diversity of plant species where the two ecosystems overlapped as they’d been left to grow.

We could hear the hum of traffic on the other side of the woods but the bird song and calls of buzzards and kites overhead were much more prominent and distracted from it.

Inside the woods, Dr Maseyk told us about some of the instruments that are in the process of being deployed to monitor environmental and biodiversity changes that will add to the multitude of data being collected to quantify the effects of the ecosystem restoration.

The tree sensor he is pointing to in the photo measures water use, light, and growth of the tree as well as other key ecological processes (such as those linked to the carbon and water cycles) that together, will help paint a picture of how certain trees are responding to changes in temperature, moisture, light, pollution, disease etc.

We were also told about various ways that the Living Lab is monitoring biodiversity across different ecosystem types.

Using camera traps to monitor wildlife in the urban woodland for example, the team has had success capturing some of the animals you expect to see in an urban environment, like foxes, squirrels, rodents etc as well as less common ones like deer and badgers (- pictured).

Dr Maseyk recounted how the cameras were also capturing interesting animal behaviour, like a magpie tackling a crayfish from the river, which it either managed to catch itself, or through a strategy known as kleptoparasitism, stole from another animal that caught it.

He went on to tell us:

"Over time, the Open Living Lab will develop a large database of biodiversity observations from these different methods and will be able to monitor the seasonal variations and how these change in response to the establishment of new habitat across the site."

Our floodplain meadow walk

We made our way from the urban woodland through to grassland next. The designated pathway (and signs) will eventually cut through the grass but for now we had to take the adjoining concrete path that met up with a Redway a short distance away.

As the sun came out for this part of the tour, we were soon beside a beautiful floodplain meadow. Dr Maseyk explained how fortunate the project was to have an opportunity to contribute to the restoration of these highly threatened habitats, not least for the myriad of environmental and social benefits they have to offer.

We were informed that the area we were walking in flooded periodically every winter, making it a great space for the OU to be keeping safe from building expansion. It was clear to see that it was also an ideal zone for observing a range or processes, habitats and nature for this dynamic living laboratory environment too.

As we took our time exploring the meadow, a botanist in our group noticed an unusual red flower among the carpet of grassland flowers. It turned out to be “Lathyrus cicera“, a pretty little inedible creeping plant of the pea family, commonly known as “Red pea vine” or “Chickling vetch”.

Regeneration of floodplain woodland

As we got closer to the river, we were introduced to another key feature of the physical Living Lab where a wet “riparian” woodland is being regenerated – i.e. a wooded area of land adjacent to a body of water such as a river.

The idea here is for the project to initiate restoration of some of the UK’s least common wooded habitat that is a vital part of the water ecosystem. It is doing this by planting appropriate native tree species such as Field Elm (Ulmus minor), Wych Elm (Ulmus glabra), English Oak (Quercus robur), European Ash (Fraxinus excelsior), Common Alder (Alnus glutinosa), and Downy Birch (Betula pubescens).

Dr Masyek explained how riparian woodland can deliver significant benefits, including: reductions in water temperature (by creating shade), increased biodiversity, reduced soil erosion, slowing of floodwaters, improved water quality, sequestering carbon and enhancing the landscape.

He went on to tell us how the 500 trees that have already been planted will be followed by subsequent plantings spaced out over time to achieve a diverse age structure to the (2,000 strong) canopy that will encourage natural regeneration. The idea being, that it will provide an important habitat for other plant, insect, bird and mammal species, in addition to capturing carbon, as the woodland develops.

It was inspiring to recognise the impact this project could have, not just in MK but also, as Dr Maseyk alludes to below, as a potential blueprint for urban sustainability across the rest of the country, let alone the world!

“Reducing carbon emissions is critical to achieving net zero, but we’ll only get there if we can pull carbon out of the atmosphere. By comparing measurements from the site with two control sites on the OU campus - one a semi-mature woodland and the other an unplanted floodplain meadow - we hope to demonstrate the real carbon capture potential of nature restoration and create a blueprint for similar projects using the many underutilised spaces in towns and cities across the UK and worldwide.”

Mast stations across the site

As we approached the end of our tour, we passed the third cordoned off site that was being prepared for a tall mast monitoring station.

Dr Maseyk described the rich source of data that these masts would be helping to capture for the Open Living Lab to complement the environmental data he had already told us about in the woodland area. The additional elements he spoke of ranged from acoustic recorders (for capturing birdsong and bat calls) to “phenocams” designed for monitoring vegetation change.

It was fascinating to hear about that technology, and the way the project was conducting such innovative research through a mix of technological, behavioural, and natural solutions in direct response to the rapid loss in biodiversity that is well documented to be due to habitat loss, climate change and other anthropogenic drivers.

Among the conversation, there was also mention of the possibility of conducting “field casts” and “virtual” tours to engage people through a blend of field-based science and distance learning (using live audio-visual broadcasting and viewer “chat” interaction), which made me wonder whether the mast stations may need to be used for more in future as the needs of the Living Lab change along with the technology facilitating it.

Insect monitoring over the floodplain meadow

As we watched dragonflies and damselflies dart over the floodplain meadow, it was amazing to hear that the Living Lab project area has been selected as one of only 100 sites nationwide to join a project call BIOSCAN that is helping to classify the genetic diversity of 1 million flying insects across the UK. Dr Maseyk explained how both the Living Lab’s wet woodland site and adjacent floodplain meadow are being used to take collections of flying insects using ‘Malaise traps’ over a 24-hour period every month as part of the project’s data collection process; marking a wonderful addition to the already rich and meaningful data the project is already collecting.

Next steps

Reflecting on my tour of the Living Lab, as I write this, I feel privileged to be a part of the project. Not only do I appreciate how vital it is to improving researchers’ understanding of how nature-based solutions can address the climate and biodiversity crises, but it has the potential to be critical in fostering students’ and the general public’s engagement with the natural world in order for us to protect it.

The Living Lab team clearly recognises that “action and demonstration” must be at the heart of their engagement programme. Hence, their ambitious plans to engage local people in learning walks (or “walk-shops” as a member of our group liked to call them) and the invitation to local schools and community groups to use the site for field trips and ecological projects (involving potential data collection activities like tree growth measurements and ecological surveys).

When fully developed, the restored woodland is expected to capture up to 20 tonnes of atmospheric carbon dioxide annually, significantly contributing to Milton Keynes’ 2030 net zero climate action goals.

Future ambitions

The project has the ambition to offer a regularly updated public-facing website, free Open Educational Resources, and access to data for teaching and research, and in Phase Two (in years 3 – 5) envisions expanding the Living Lab into a globally recognised centre for nature recovery education, involving increased data collection, multidisciplinary research, and broader educational outreach.

But… as exciting as all of this sounds, none of it can happen without our community getting behind it and proving its worth first.